It is one of the highlights of the Warsaw Rising Museum. Every visitor raises their head to ponder on its story. The Liberator piloted by Cpt. Zbigniew Szostak completed six vital airdrops of weapons, ammunition and medical supplies over fighting Warsaw in 1944. This one-to-one scale replica of Szostak’s Liberator pays homage to the bravery, skill and courage of the crew who gave their all to help Warsaw during its greatest hour of need. All seven crew members were sadly killed in action over southern Poland on 15 August 1944, by a Luftwaffe night fighter during their return flight back to Brindisi, Italy.

The largely unsung heroes of this article had many pre-war hours of flying combined between them. The crew commander, Cpt. Zbigniew Szostak graduated first in his class at the Polish Air Force Academy and became an airline pilot for LOT Polish Airlines. He would leave his mark in history as a renowned Polish bomber squadron pilot. He must have been truly dedicated to the cause as he did not refrain from flying having accomplished fifty missions. He carried on.

Szostak was born in Warsaw where he went to the Rejtan Secondary School. He lived in Żoliborz District at 29, Wojska Polskiego Street. Were these places the ones he was trying to get the sight of flying over burning Warsaw on the night of 14-15 August 1944? Or was he deeply in thought about his wife who was staying alone in Paris at the time and was bringing up the son that he would never have the chance to see?

Zbigniew Szostak (11.11.1915-15.8.1944), First pilot of Liberator KG890, decorated twice with Virtuti Militari Cross, four times with the Cross of Valour and a Distinguished Flying Cross. Photo: public domain

Zbigniew Szostak with his wife – Krystyna née Mysiak. Before 1939. Photo: Private archive of Wojciech Krajewski

His charisma emanates from the memories collected by Szostak’s flying mates in an article published in “Skrzydlata Polska” (Eng. Winged Poland) (Issue 19, 13.5.1961) when it comes to the period they flew together in the Polish squadron known as the 1586 Special Duties Flight from Brindisi (IT) to Warsaw that was consumed by flames and still fighting for freedom.

“Zbyszek was always an airman full of courage and fervor, however at the time of our missions to Warsaw he left us in awe. We were all terribly exhausted. Though he had no supernatural forces, he turned into a man of iron. He would return to the base late in the morning, had a nap and later in the afternoon was back on board. His playfulness vanished forever and we lost him as a mate who was always first to have fun. Over Warsaw that was consumed by smoke and flames he asked the second pilot to take the steer and took over the role of the navigator to steer the aircraft towards small portions of the city where the defense still held. He was the one to know the city the best of all crewmembers. We can imagine how much it must have cost him, for a first class pilot as he was, to ask others to take over the steer flying on low level over a target where they were subject to anti-aircraft fire (…)”

Bryan Desmond Jones, a SAAF bombardier during Warsaw Airbridge recalled that meeting Szostak at their briefing before leaving to Warsaw on 13 August 1944 really brought up the emotions. His testimony is screened as a part of the permanent exposition at the Warsaw Rising Museum:

“Right at the end of the briefing, the wing commander invited a Polish squadron leader to address us. And he stood up and very emotionally, I can see him now, he was very emotional. He said „My country, Poland, is in serious trouble. And I plead with you – South African and British gentlemen – to help Poland tonight.” [in: Oral History Archive (AHM), interview with B.D. Jones registered on 2.8.2008 in Warsaw]

Second pilot Józef Bielicki must have loved flying above all as he was only 17 when he got his flying license. He was born on 12 February 1922 in Warsaw. He was baptized in a nearby St. Alexander Church which is only partially preserved in our present day. His home at the crossroads of Matejki and Wiejska streets no longer exists. When WW2 broke out he was studying at the Air Academy for Cadets in Krosno. His wartime trail led him across Romania, France (Lyon-Bron and Rouen military bases) to Britain (Gloucester and Blackpool airbases). It is worth noting that his cousins also served in Royal Air Forces, namely Władysław Bielicki (pilot, 316 Sq) and Czesław Rajpold (gunner and radio operator of Wellington IC XW-N (DV765) whereas some of his family members fought in the Warsaw Rising. Therefore, seeing fighting Warsaw in flames was surely tearing his heart apart. He was only 22 then and even though his family came from Bielice, far to the north–east of Warsaw, he spent most of his life in the capital of Poland. In February 1944 he volunteered to join the 1586 Special Duties Flight where he took part in 45 air operations.

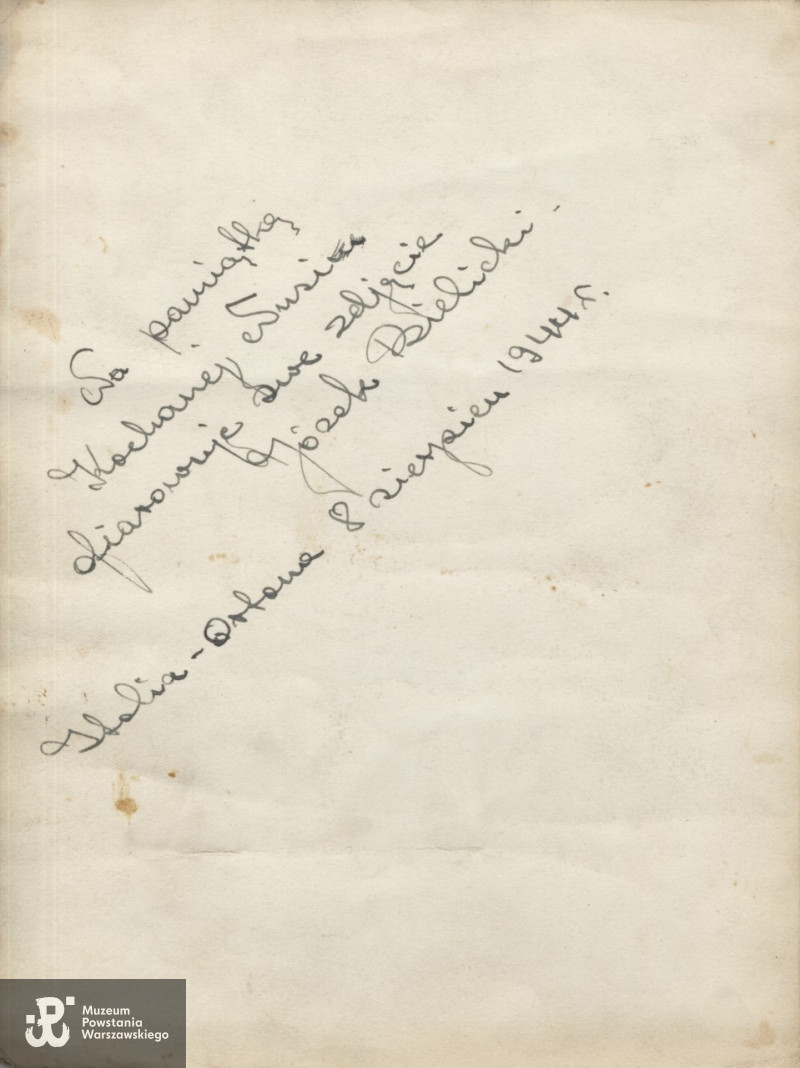

There is a fascinating story behind his photograph that is presented at the permanent exhibition of the Warsaw Rising Museum now. Józef gave the photograph to his beloved girl just a week before the tragic flight to Warsaw which turned out to be his last mission. At the back of the photograph he wrote:

I offer the photograph of myself for my Beloved Nusia

Józek Bielicki. Italia- Ortrona 8 August 1944

His loved one, Nusia’s full name was Florentyna Irena Borkowska. She was 24 then and worked as a driver in the 316 Transport Company (WAS) under the 2nd Polish Corps. What happened to her? For sure it is known that she was born on 7 March 1920 in Pakość upon the Noteć River. After the outbreak of WW2, already in 1939 her Father was killed whereas Florentyna, her mother, grandmother and sister were sent to Siberia in the very first transport orchestrated by the Soviets on 10 February 1940. She was deported far to the East near Arkhangelsk to a Soviet GULAG labour camp. In order to survive she was a forced labour logging worker. There, deep in the Siberian inhumane land she lost her grandma and later while trying to join the Anders Army, her mother passed away. She served in the 2nd Polish Corps all along its trail across Iran, Iraq, Palestine, Egypt and Italy. She became a driver in the 316 Transport Company and it was there where she met Józef Bielicki who as a Polish pilot quartered in Brindisi with the 1586 Special Duties Flight. Their happiness was short-lived, though. Józef did not return from his flight to Warsaw on 15 August 1944.

She learnt that he had been killed in action, but the full details behind his final flight were probably not revealed to her until after the war. After losing her soul mate, she never got married.

Józef Bielicki (12.02.1922-15.8.1944), 2nd pilot of Liberator KG890, decorated three times with the Cross of Valour and the Order of Virtuti Militari (posthumously). Photo: Private archive of Janusz Bielicki

The back side of the photograph from 8 August 1944. Photo: Private archive of Janusz Bielicki

Corporal Florentyna Irena Borkowska, driver in the 316 Transport Company of the Anders Army in Italy. The Beloved of Józef Bielicki. The photo comes from the book by Bronisława Kwaśnicka: „W służbie ojczyzny: Polska Wojskowa Służba Kobiet w 2.Korpusie PSZ: 316 kompania transportowa 1942-1946, wyd. 1988, Nowy York."

Navigator Stanisław Daniel was the eldest member of the crew aged 34-years-old. He was an experienced airman. He had successfully completed his tour of operations and had a chance to return to Britain. However, he volunteered to keep doing his work. An honourable and courageous decision which would sadly cost him his life.

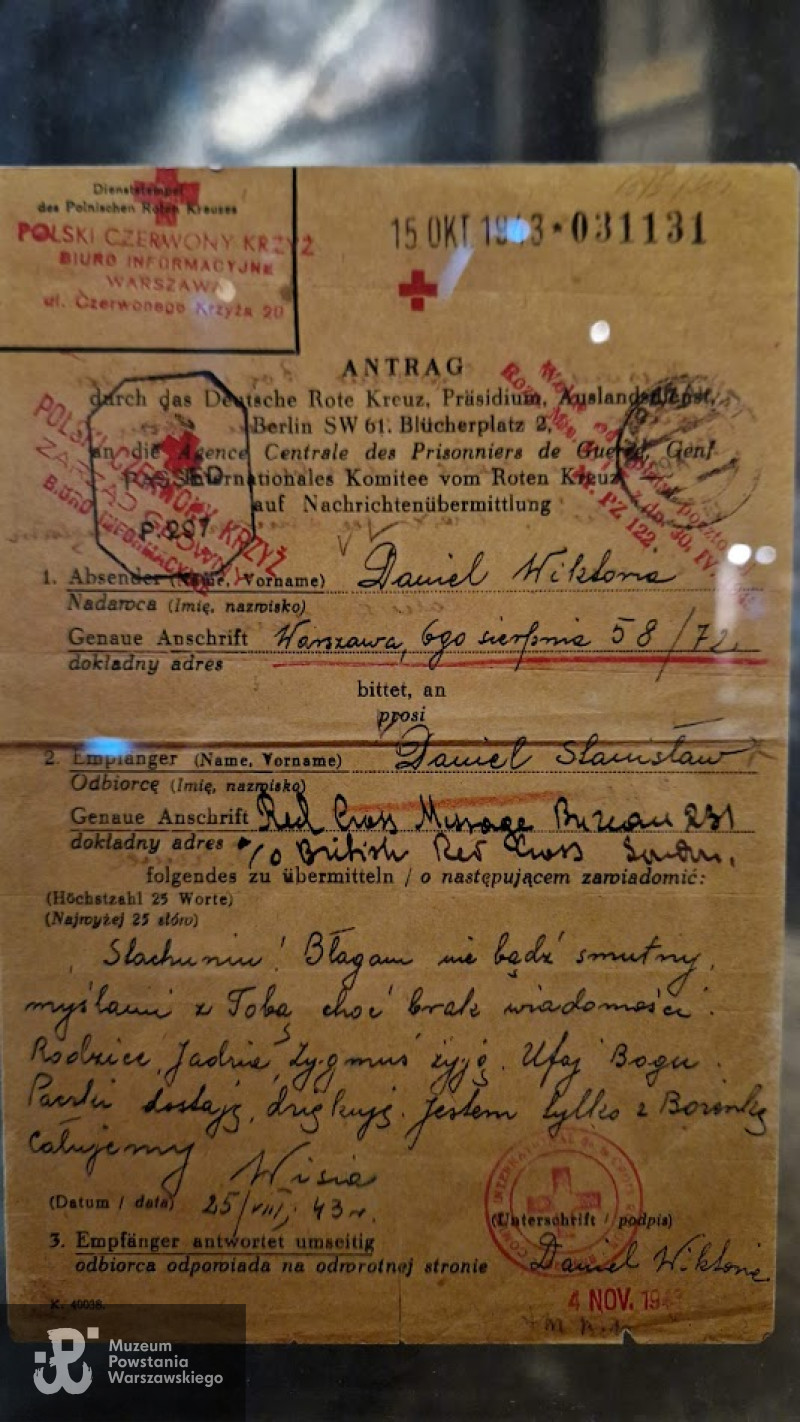

He was born in 1910 in Vladivostok (RU) and once Poland restored sovereignty after WWI, he had a chance to go back to his family homeland – Poland. Having graduated from the legendary Air Force Academy in Dęblin, he worked as an instructor for military aviation trainees. Looking at his prewar photographs we can see how happy he was with Wiktoria Daniel, née Górka, his wife. They had no children so they would spend a lot of time with Bożenka, Wiktoria’s niece. Their heartbreaking wartime letters are presented at the permanent exposition of the Museum.

Stanisław Daniel (29.3.1910-15.8.1944), navigator of the Liberator KG890, decorated with Virtuti Militari and twice with the Cross of Valour. Photo: public domain

Stanisław Daniel with his wife Wiktoria and their niece Bożenka. Warsaw before 1939. Photo: Private archive of Wojciech Krajewski.

In 1939 when the Polish military personnel were being evacuated towards Romania, Stanisław Daniel was parted from his wife. They promised each other to meet at the ‘Hotel George’ in Lviv. Unfortunately, they reached the city of Lviv not at the same time and in the chaos of the evacuation, they had no chance to meet… They would never see each other again. Stanisław Daniel made it to Britain through Romania and France. He joined 1586 Special Duties Flight. He would be engaged many times in the transport of the Silent and Unseen as well as airdrop missions over occupied Poland.

Wiktoria survived the German occupation in Warsaw. Together with Bożenka they were kicked out of their apartment by Germans during the Warsaw Rising. They were deported to a forced labour factory near Berlin but luckily managed to return to Poland in 1945. Wiktoria Daniel learnt about her brave husband’s tragic death a few years after the war had ended.

One of the letters sent by Wiktoria Daniel to her husband during WW2. Photo: Warsaw Rising Museum Collection

Józef Witek served as a radio-operator on board of the Liberator KG890. His military career led through the steppes of Siberia in Russia. He was born on 21 April 1915 in Brzeszcze. He started his flying adventure in 1937 in the 5th Air Regiment in Lida near Grodno. Mobilized as a soldier when WW2 broke out, he was captured by the Soviets and sent to Arkhangelsk. When the Anders Army was being formed he got a chance to escape from the Siberian hell-on-earth and continue his military training in Great Britain. He was 29 when he was killed in the crash on 15 August 1944.

Józef Witek (21.4.1915-15.8.1944), radiooperator of the Liberator KG890, decorated with Virtuti Militari and three times with the Cross of Valour. Photo: public domain

The airmen training in Great Britain during WW2. Józef Witek kneels, second from the left. Photo: Lucjan Lubas Collection

Wincenty Rutkowski was only 23 years old when he flew to Warsaw in 1944. He was born in Zakrzów on 26 February 1921 and he fulfilled his dream about flying when studying in the Air Academy in Bydgoszcz. As the other members of the Liberator KG890 crew he came to Britain and then as a mechanic he joined 1586 Special Duties Flight.

He volunteered to participate in the air operations before the Warsaw Rising. The flight operated on 14-15 August 1944 was his eighth flight. He was killed in action after bailing out from the burning Liberator.

With a bit of luck he would have survived. Unfortunately, the burning bomber was flying at low level over a hill when Rutkowski jumped out. He had no time to open the parachute. Had he bailed out a second later, where there was a cliff below, he might have been the only survivor of the fatal flight.

Wincenty Rutkowski (26.2.1921-15.8.1944), a mechanic of the Liberator KG890, decorated with the Order of Virtuti Militari and the Cross of Valour. Photo: public domain

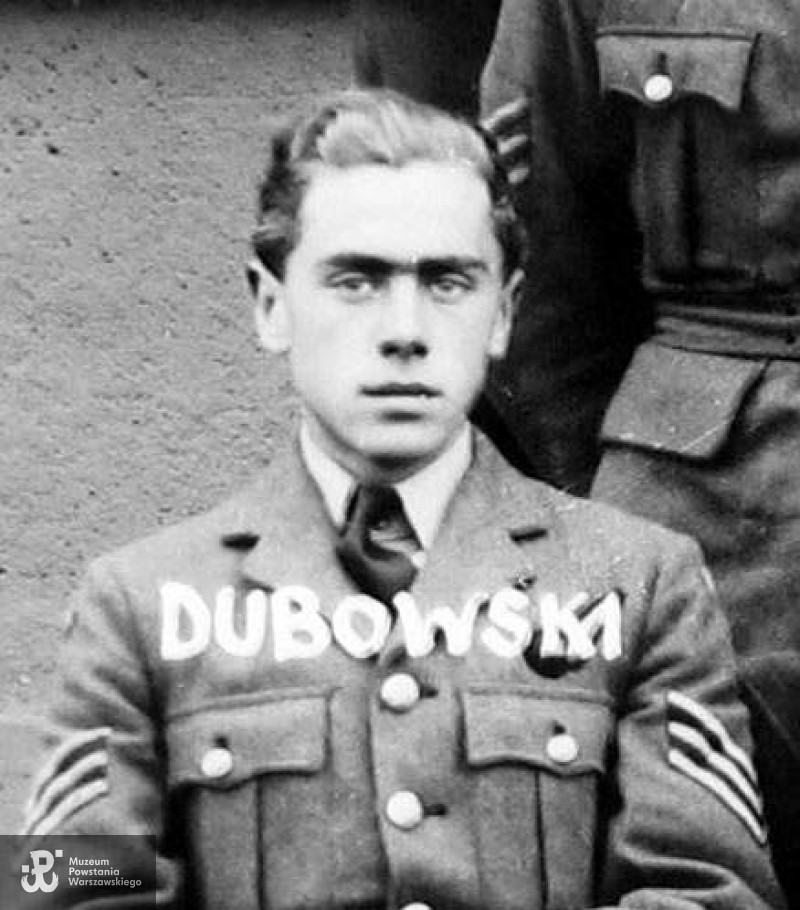

The youngest member of the crew was Tadeusz Dubowski who was only 21 at the time. He was born on 7 July 1923 in Cracow. Trained in Britain, he was ready to join the Polish Special Duties Flight. He served as a dispatcher and was responsible for manual disposal of the parcels through the back of the fuselage. Even though the Liberator could carry only 12 containers 150 kilo each and 12 parcels 50 kilo each, every load destined for the Insurgents in Warsaw was p r i c e l e s s.

Tadeusz Dubowski (7.7.1923-15.8.1944) bombardier of the Liberator KG890, decorated with the Order of Virtuti Militari and four times with the Cross of Valour. Photo: public domain

A 28 year-old Stanisław Malczyk was the gunner on board of the Liberator KG890. He was born on 31 January 1916 in Filipowice. He had just finished an RAF training course for gunners during WW2. At the time of the Warsaw Rising he was six times over Warsaw. As a rear-gunner he held the loneliest and coldest place onboard – at the very end of the fuselage. He was responsible for protecting the aircraft that flew through the night skies largely defenseless and without the mighty support of the allied fighters. A constant focus during a 12-hour flight were definitely quite a challenge and the fact that he was always ready to fly to fighting Warsaw prove he was a truly b r a v e man. Stanislaw Malczyk bailed out from the burning Liberator as the rest of the crew and shared their tragic fate.

Stanisław Malczyk (31.1.1916-15.8.1944) rear-gunner of the Liberator KG890, decorated with the Order of Virtuti Militari and four times with the Cross of Valour. Photo: public domain

The Szostak’s crew did not return to the base in Brindisi. Germans caught their aircraft through the radar and send a night fighter to eliminate it. The drama took place over Bochnia near Cracow. It was a fight against impossible odds and the crew had small chance to make it out. The pilot of the Liberator was desperately trying to avoid the German fighter that was attacking them. To no avail. The Liberator was hit and set on fire. When the crew bailed out the Liberator was already at low level so the parachutes did not open when they jumped out. Sadly, the airmen all fell to their deaths.

Historian Wojciech Krajewski made an attempt to reconstruct the last moments of the crash in a book “Powietrzna walka nad Bochnią” (2006) [Eng. Air battle over Bochnia], where he presents a detailed story of the Liberator KG890. He managed to collect several eyewitness accounts that made it possible to understand what happened on 15 August 1944. A testimony given by Stefan Szydek, who was 14 years-old at the time, says a lot about the drama that took place:

I was woken up by a huge roar of the engines from an aircraft that glided near the house at 200-300 meters heading east from the west to Nieszkowice Wielkie. It was burning like a torch so the light filled the room as if was a day. I rushed outside but it was all over. The aircraft flew away and then suddenly went off like a ball of fire.

[in: Krajewski. W “Powietrzna walka nad Bochnią”, Bochnia 2006, page 81]

Two days later on 17 August 1944 the inhabitants of nearby villages of Nieszkowice Wielkie and Pogwizdów took part in a solemn funeral to honour fallen airmen though German authorities had strictly forbidden any ceremony.

The funeral of the crew members of Liberator KG890 at the cemetery in Pogwizdów, 17.8.1944 Photo: Warsaw Rising Museum Collection

After WW2 the remains of the airmen were taken to the Rakowicki Military Cemetery in Cracow where they rest to this day. The local community has never forgotten about the crash and remembrance about this event constitutes even today a vital element of their identity. In 2004 a local school was finally named after the brave Crew members of Liberator KG 890, and took the name of “Polish Airmen” (the attempts were refuted for many years by communists after WW2): www.nieszkowicewielkie.szkolagminabochnia.pl/patron/

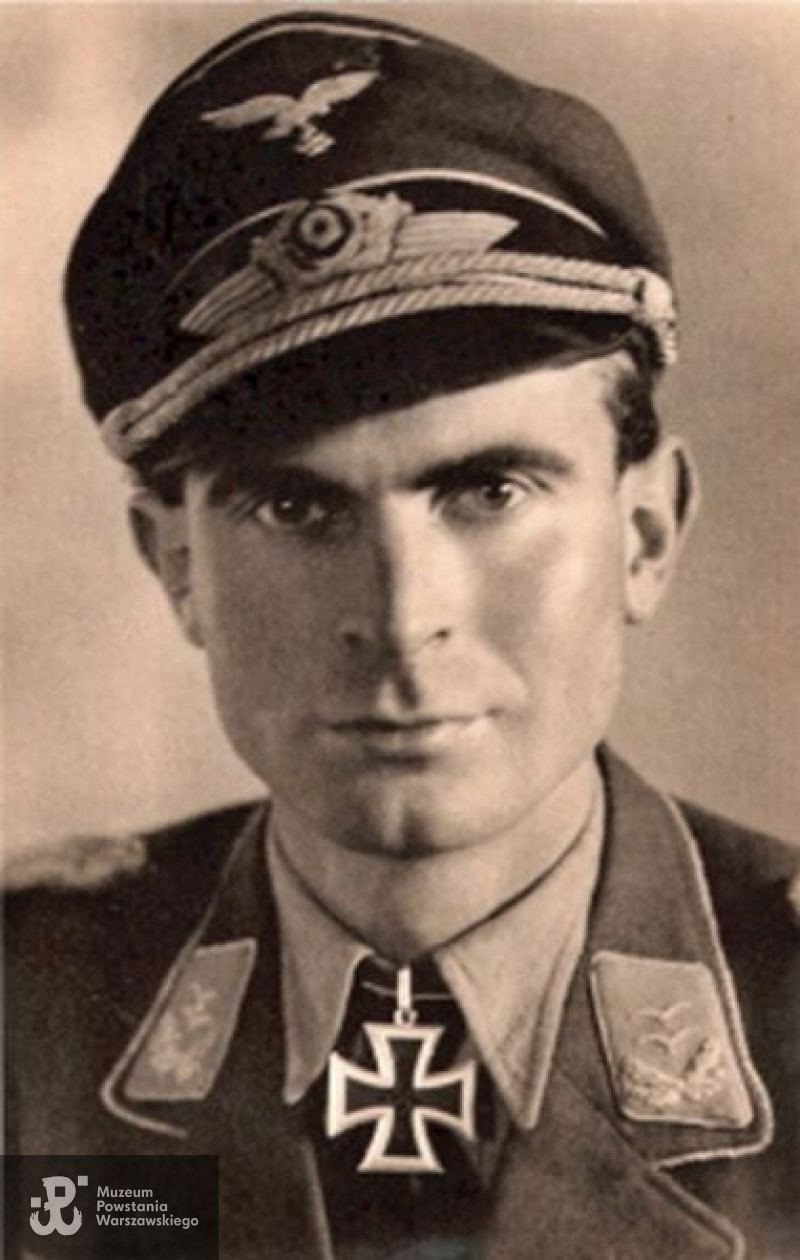

The flight operated by the crew ended so abruptly because of Oblt. Gustav Eduard Fransci, a Luftwaffe night-fighter pilot. Interestingly, Fransci shot down all three losses to 178 Squadron on 14-15 August 1944, with the Liberator KG890 being his prey as well. He survived WW2. Captured by the allied forces in 1945, he was freed rather quickly and started a ‘normal’ life in Germany. He worked as a specialist in fixing TV sets. His life ended in 1961 when he got drowned trying to save his fiancée in Spain. He was 47.

Oblt. Gustav Eduard Fransci, pilot of the Luftwaffe fighter. The man behind the tragic death of the Liberator KG890 crew that was downed by him after an air battle at 1.38 am according to German war documents. Photo: tracesofwar.com

The Western Allies would keep the airbridge with Warsaw from 4 August to 22 September 1944. The airmen who safely returned to the base would never forget the sight of Polish capital devoured by flames, the smoke that filled their cabins and deadly air battles with German night fighters.

On 14 August 1944 twenty six crews took off towards Warsaw from the British Campo Casale airfield in Brindisi. The Szostak’s crew was one of them. Every mission involved challenging logistics and so much was at stake as the people of Warsaw still needed help. The tireless airmen of the Polish Special Duties Flight, British Squadrons (178 and 148) and South-African Squadrons (31 and 34) bore huge losses.

The Polish airmen were the ones who flew the most and they paid the highest price. Cpt. Szostak’s crew was the first Polish crew to be ‘missing’ (their death confirmed shortly after). There were 14 Polish crews that were killed in action in the Warsaw Airbridge . Only two made it through.

In Freedom Park next to the Warsaw Rising Museum there is a monument in remembrance to 112 Polish, 90 British, 43 South-African and 12 American airmen who sacrificed their lives in air-drop missions over fighting Warsaw in 1944.

Glory to the Heroes!