In 1944, during the Warsaw Rising, the Western Allies launched a special operation known as the Warsaw Airlift to drop supplies such as weapons, amunition, medicines, food and clothes to the Poles struggling for freedom in Warsaw, the heart of their occupied country. Four-engine bombers – Liberators, Halifaxes and B-17s had usually seven crew members on board. The aircrafts took off from the airfields in Southern Italy and (once) from Great Britain. The airlift was an example of superhuman heroism. What made it all possible? Skills, cleverness, luck and… faith in God, as the crew members recalled.

Halifax used by the Polish airmen. Brindisi Airport. Photo: Author Unknown / Warsaw Rising Museum

Halifax used by the Polish airmen. Brindisi Airport. Photo: Author Unknown / Warsaw Rising Museum

The 1586 Polish Special Duties Flight, Royal Air Force (RAF), South African Air Force (SAAF), Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) and United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) squadrons were involved in the Warsaw Airlift.

The operation started on 4 August 1944. Then, after 10 days on the night of 13/14 August 1944, the aircrafts were sent again towards occupied Poland. The last flight took place on 21/22 September 1944. As for the American operation Frantic 7, it was launched on 18 September and it was operated by the USAAF from the British Isles.

Liberator. Photo: Author Unknown / Warsaw Rising Museum

Liberator. Photo: Author Unknown / Warsaw Rising Museum

A round trip of twelve hours and a distance of three thousand kilometers was covered. They flew over enemy territory at four thousand meters above sea level (ASL). Many times they were forced to fly at two hundred meters due to enemy searchlights chasing them. They had to be at a hundred meters over dropping zone to drop supplies they had on board.

Halifax. Photo: Author Unknown / Warsaw Rising Museum

Halifax. Photo: Author Unknown / Warsaw Rising Museum

Warsaw on fire was a powerful image that stayed in the memory of the airmen. F/Sgt Antoni Tomiczek who served in the 1586 Polish Special Duties Flight Squadron underlined, in one of the interviews after the war, that a big ball of fire over Warsaw was discernible already at 180 km from Warsaw.

Pilot William Hayden Jones (RAF 148 Squadron) said that „it seemed to be one ball of fire. With a lot of smoke, flashes, and... flares.” George Robert Adams (RAF 178 Sq) recalled that „we could see through the hole–s in the clouds the flames coming out of the city.” Maurice Sanders who was on board of Liberator KG-938 „A” on 15 August 1944 over Warsaw said that: „The city was on fire, there was a lot of smoke and haze around. The Germans were shooting at us all the time as we went in and of course we were within range of rifle fire let alone anti-aircraft guns.” Antoni Tomiczek recalled: „The red heaven was full of the light of the search lights – the white ones were looking for us up high while the blue ones – low. The Germans knew that we were flying at different levels. When we almost reached Warsaw I had blue search light on my side and some space in front. They did it on purpuse, no search lights at some point to catch us in this hollow space.”

On the night of 27/28 August 1944 the liberator VI GR-S (KG 927 „S”) with Major Ruman as an airgunner on board was flying at 91 meters above Warsaw in order to avoid AA fire. They dropped supplies in the Mokotów district and descended to 30 m above the ground aiming at hiding from AA fire in the smoke of the fires from burning buildings. The liberator turned left over the City Centre and the Main Railway Station and headed westwards. Due to AA fire many systems went down and only three engines were still working. The crew managed to accelerate only by 16,4 km/h and reached 244 m ASL after a quarter of an hour. They found it impossible to close the bomb doors.

Near Cracow the aircraft was hit again by AA fire which led to another engine catching fire. They were in dire straits but decided not to bail out. With only two engines still working they headed southwards at 1,4 – 2,43 km ASL. Though they lacked fuel and had encountered that many adversities they reached the South of Italy and the Campo Casale air base near Brindisi. When they touched down it turned out the brakes were broken and the liberator could not lose its speed. They could have crashed straight to the sea from the cliff! The pilot, F/Lt Jan Mioduchowski, performed an excellent maneuver and the Liberator hit the ground with one wing and stopped.

Two engines were torn out and the fuselage broken in two. The left engine was in flames… But seven crew members were safe, luckily. Only F/O Józef Bednarski who served as a dispatcher had been wounded over Warsaw. It turned out later that they would have had enough fuel only for a 5 minutes flight left. Their parachutes were riddled with holes so it was good they had not decided to bail out. It was 5.20 am. The mission took 10 hours and 38 minutes. Tadeusz Ruman recalled: „It was a miracle that we went back. When I left the aircraft, I kissed the ground and thanked God. He saved my life.”

Maj. Tadeusz Ruman. Fot. Author Unknown / Jan Ruman collection

Maj. Ruman claimed that his life was spared so many times because of a small 1,7 cm aluminium holy medal with Saint Juda Apostle, Patron Saint of desperate cases and lost causes. It is exibited at the Warsaw Rising Museum under the fuselage of a one-to-one replica of Liberator KG 890.

Holy medal that saved Tadeusz Ruman’s life during Warsaw Airlift. Photo by Warsaw Rising Museum

When visiting the Museum save some time to reflect on the other exhibits donated by Tadeusz Ruman as well, such as his sunglasses or the Distinguished Flying Medal, he was decorated with it, among others, in recognition of his last flight in the Warsaw Airlift.

During the Warsaw Rising he took part in six airdrop missions over the city of Warsaw and one over the Kampinos Forest.

Tadeusz Ruman’s sunglasses. Photo by Warsaw Rising Museum

Distinguished Flying Medal that Tadeusz Ruman was decorated with. Photo by Warsaw Rising Museum

Distinguished Flying Medal that Tadeusz Ruman was decorated with. Photo by Warsaw Rising Museum

William Hayden Jones (148 Sq RAF) took part in two flights to Warsaw: on 13/14 August and on 14/15 August 1944. He flew Halifax JP-254 „D”. The second time finding dropping zone was quite a challenge due to low visibility and heavy AA fire. The tail elevators were half knocked off, onboard communication and signal lights got broken. The aircraft could not make any sharp movements. The crew kept cool. The flight took 9 hours 40 minutes.

F/WO George Robert Adams (178 Sq RAF) was twice above Warsaw as well: „We were being fired at because we were low, we could see Germans firing at us, we could see the guns operating at us. Our guns were able to shoot at the search lights which saved us because otherwise, if we were hit by the search lights, we couldn’t see anything and we would have crashed.”

There was an aircraft in front of them which was shot down. Germans have been concentrating at firing at that aircraft and when it blew up, a part of that aircraft hit them. There was no time to estimate the damage it caused. They had to escape into safety as soon as possible. The pilot concluded that flying over the smoke of the fires would lead to being traced by Germans so for the first five minutes they were flying through the smoke and flames and then finally they realised that their aircraft had been affected by AA fire. The damage was not huge but they could not risk losing fuel. They decided to find an air corridor not going up to high. They used all the amunition above Warsaw so encountering Germans was not advisable. They managed to safely return. „I think these operations were most difficult we did”, recalled G.R. Adams.

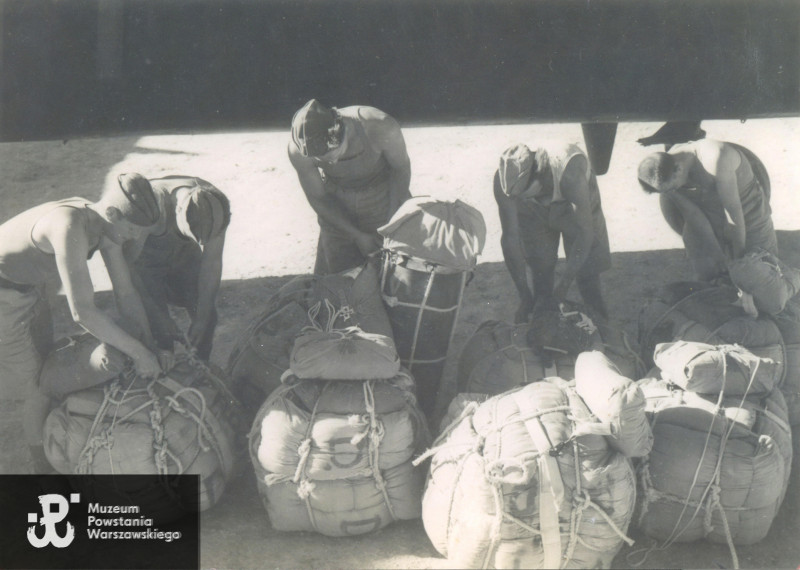

Loading supplies before leaving to Warsaw. Photo: Author Unknown / Warsaw Rising Museum

Loading supplies before leaving to Warsaw. Photo: Author Unknown / Warsaw Rising Museum

Also, the 31 Sq SAAF’s Liberator KG-872 V under Cpt. Senn’s command was in big trouble. The crew managed to drop twelve containers with supplies but due to heavy AA fire the capitain had terrible thigh injuries. Lt Symmes had to use extinguisher to put down fire next to one of the engines. He got hurt in his face doing that while a gunner was hit in his arm. Many systems went down and they were preparing to bail out when the pilot managed to escape safely from AA fire whereas Sgt. Owen, the gunner, destroyed enemy’s search light with one effective shot. They were on their way back to the Celone Airfield in Italy, though they had no navigation instruments left working. They could only rely on the radio systems. The flight took 11 hours and 23 minutes in total.

Loading supplies before leaving to Warsaw. Photo: Author Unknown / Warsaw Rising Museum

Loading supplies before leaving to Warsaw. Photo: Author Unknown / Warsaw Rising Museum

Sgt Antoni Tomiczek was sent to Warsaw three times. The very first one, on the night of 22/23 August 1944, was particularily dangerous. He was the pilot of Halifax JD-171 B. He recalled: „We had to wear oxigen masks all the time. Sitting with parachutes and all of that was very uncomfortable. If there was no second pilot, one had to fly two flights one after another if the weather was good. If there was someone to change you, namely a second pilot, then three nights in a row, with one break”. On that night he had no support, no second pilot. It was quite a feat to run away from the searchlights chasing you all the time. „The enemy knew that we flew at different levels so they waited until an aircraft found itself in the middle of the empty space.” That is what happened with the Tomiczek’s Halifax. The search lights shone so much that the pilot got temporarily blinded. The Halifax was under heavy AA fire. The pilot tried to make a 90 degree turn but the Halifax lost DWT and was diving towards the ground. Fortunatelly, the aircraft restored the controllability and responded to the pilot’s control to move up. The stress and physical effort were difficult to cope with: „I went blank and when I restored consciousness we were already at 1000 meters ASL and I could finally cruise at an even flight level.”

They were above the right river bank of the Vistula river. The German AA fire was still active but did little harm at that point. The pilot asked the crew whether no one suffered from all these twists and turns. Neither gunners responded, nor the navigator – P/O Leon Schedlin-Czarliński, so Sgt Tomiczek asked Sgt Mieczysław Posłuszny to check what was going on. He returned with the news that they were ‘lying’. A momentary fear turned into relief as it appeared that they had only fallen from their seats as they had not had their belts fastened. Unfortunately, they had run out of ammunition. “10,000 bullets were all gone”, the Pilot remarked. It was a bad omen as the mission was not over. They had to drop the supplies they had on board.

The Halifax turned back towards the left river bank of the Vistula river and dropped the containers in the area of Marszałkowska Street. There was no time for feelings of comfort then, however. The mechanic shouted that the fuel from the right fuel tank was lost, most probably due to AA fire. The pilot decided to use the left fuel tanks anyway though they were convinced they might have been already empty. Tomiczek knew that this may be futile anyway so he asked the crew by whom they would prefer to have been captured: Germans or Soviets?. They chose Germans, as all but one – the navigator – had already been POWs in the Soviet Union and had no intention to fall in the Soviet hands again. Tomiczek asked to prepare parachutes and started to head over territory that was in German hands. Flying above the Tatra mountains they even reached 6,600 m ASL. Listening to the engines, he realised that the left fuel tanks must have been still in good shape. When they reached the Adriatic Sea they were extremely relieved. Even if the engines had stopped, they could have made it to the Italian shore. The Halifax touched down in Brindisi after a 10 hour 45 minutes flight.

Sgt Tomiczek was so exhausted that he found it impossible to chew the scrambled eggs he was served.

Lt Bryan Desmond Jones went through the moments of horror on the night of 13/14 August 1944, during the only one flight he had to Warsaw.

The Allied airmen who were at the base in Southern Italy learnt on 13 August 1944 that they were assigned to the crew of Liberator EW-105 G. They were all excited. They thought they would be sent to Southern France.

In Brindisi they went to the operation room where they saw a map of Europe. And there, starting from Brindisi there was a black tape – the route marker, across the Adriatic, across Albania and Romania, cutting back into Hungary, Czechoslovakia, over the Carpathians, to Warsaw. They thought „Wow, who are those crazy guys to do that?”… They got the answer right away. „As it turned out we were the ones… We hardly knew where Poland was”, recalled Lt B. D. Jones.

The danger was about the icing on the wings, the leading edge of the wings that would press the aircraft down. When they got closer to Warsaw, they were making for the middle of the Vistula, as they were told that that was the safe thing to do. Then suddenly, they were attacked and lost the first engine.

Lt Jones was a navigator. He was calculating and doing adjustments to the course. At some point he was lying on his stomach and looking out: „You could see there were fireworks going ahead. You could see the search lights coming up, catching you. You couldn’t duck or dive flying because you’d bump into one of your other aircraft. The fire’s coming and you were flying, deliberately flying into it.”

They dropped supplies from 400-450 feet. With bomb bays open and engine throttle back to 135 km/h, it was still very difficult to steer the aircraft at such slow speed. Jones recalled: „ I don’t want to give the idea that I wasn’t frightened. I was frightened. But I was so busy with doing the calculations and taking pictures and that, and reading that I don’t remember that. I can just remember the bullets going into the aircraft, I can remember the gunner calling at the back „Skipper, I’ve been hit in the arm. I can’t rotate the gun.”

They dropped the load, and they could feel the aircraft lift but just then another engine was hit. “All of a sudden, everything went black. All the hydraulics were shot away, there was no light. Under the belly of the aircraft ther was a scraping, grinding noise.”

The Liberator would not rearch Brindisi in such a state so they were forced to land on a Warsaw airfield. F/Lt R.R. Klette managed to touch down somehow. Lt Jones lost conciousness for a while, and when he woke up, he heard the other crew members saying that they would not manage to get him out as he seemed trapped in the crushed nose of the aircraft. After a while, F/LT Klette shouted to him to find an axe and chop his way out. So he did and was free again! For a moment. Germans came to the site and were shooting at them.

„Suddenly, remember we’re on the airfield, the search lights come on, shining on us and they start firing at about that height, one metre say. And we jumped, dived down and we’re crawling away like this.” Surrounded by the enemy Lt. Jones bargained with God to save him: „Take me back, God, and I will enter the Church, I’ll be a minister. That’s what I’m in. Please, Lord.”

The Germans came closer. W/O L. E. D. Winchester and W/O H. J. Brown were wounded. For H.J. Brown little could be done, he was already dead. The remaining SAAF crew members were captured, interrogated and then sent to Łódź. The only book they had with them was the Bible that Jones had received from his parents. The book got very popular. Some even read it for the first time in their lives.

After the war Bryan Desmond Jones returned home and became a pastor. As he promised.

Polish airmen standing next to a Halifax in Brindisi. Photo: Author Unknown / Warsaw Rising Museum

Polish airmen standing next to a Halifax in Brindisi. Photo: Author Unknown / Warsaw Rising Museum

Michał Tomasz Wójciuk

The above text is the translation of the original article written in Polish by Michał Tomasz Wójciuk, historian at the Warsaw Rising Museum: https://www.1944.pl/artykul/nieprawdopodobne-historie-ktore-wydarzyly-si,5161.html